The Architecture of HQS Tasks

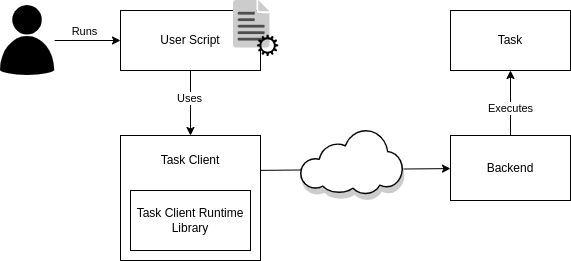

The HQS Tasks system is composed of a client and a backend part. For a better understanding of the remainder of this documentation, we first describe the roles of these components and how they interact with each other.

The Task

The task is the actual computation whose result the user is interested in. A task is used by writing a Python script that uses the client package of the task. The client package instructs a backend to schedule the execution of the task with the desired parameters and fetches the result as soon as it is available.

The Client Package

The task client package is, simply speaking, the part of HQS Tasks that runs (usually) on your local machine. The client package is specific to the actual task (or a group of tasks) that you want to execute. Running a task using the corresponding task client is as easy as calling a local function, while leveraging remote computational resources.

The task client packages for different tasks all use the same task client runtime library, which ensures a consistent interface for the configuration of HQS Tasks across a wide variety of tasks.

The Backend

There are different types of backends to execute tasks, as one of the main purposes of HQS Tasks is to make it possible to run them in various powerful remote computing environments and access them as simply as calling a local function.

In the task client runtime you configure which backend is to be used. This information is used to communicate with the actual backend.

Depending on which backend we are talking about and how your setup looks like, this backend is usually hosted somewhere else, such as in the cloud (see REST) or in an on-premise high-performance compute cluster (see SLURM).

Also, the task implementations (the actual computation to be performed) are deployed in the backend, or in a way the backend can interact with (which is, of course, again dependent on the concrete type of backend).

The backend then takes care of actually executing the tasks submitted by the task client, and will also manage the necessary provisioning (a.k.a. reservation or allocation) and de-provisioning (i.e., freeing) of the hardware resources before / after the task execution.

It can furthermore keep track of the execution process and gather the results. However, this is always initiated from the client, which we will describe below.

Communication Between the Client and the Backend

Let us briefly go through the sequence of executing a task in a typical setup, where the backend is hosted remotely.

-

Submission: The client tells the backend that a new task execution should be started. The so-called task execution request bundles the information required to do so, which comprises the name (and version) of the task, what the input is, and which hardware resources shall be provisioned.

-

Observation: The client periodically asks the backend for the state of the task execution; most importantly, whether it has finished.

-

Fetching Results: Once the task has finished, the client asks the backend for the results: if it was successful, and – depending on that – either the task's output or an error report. Also, the task log and some metrics are provided as meta information, all of which is composed in the so-called task execution response.

One important thing to note here is that there is no active communication from the backend to the client. It is always the client asking the backend for any "news," not the backend communicating them to the client actively. The benefit of this behavior is that you do not need to worry about losing network connection while a computation runs. As soon as a connection is available, the client is able to catch up on the state of the computation.